Ghost Nations

Three books, three eras. Is it about time we called Taiwan what it is. China won't like it. But perhaps it's time we stopped trying to please China.

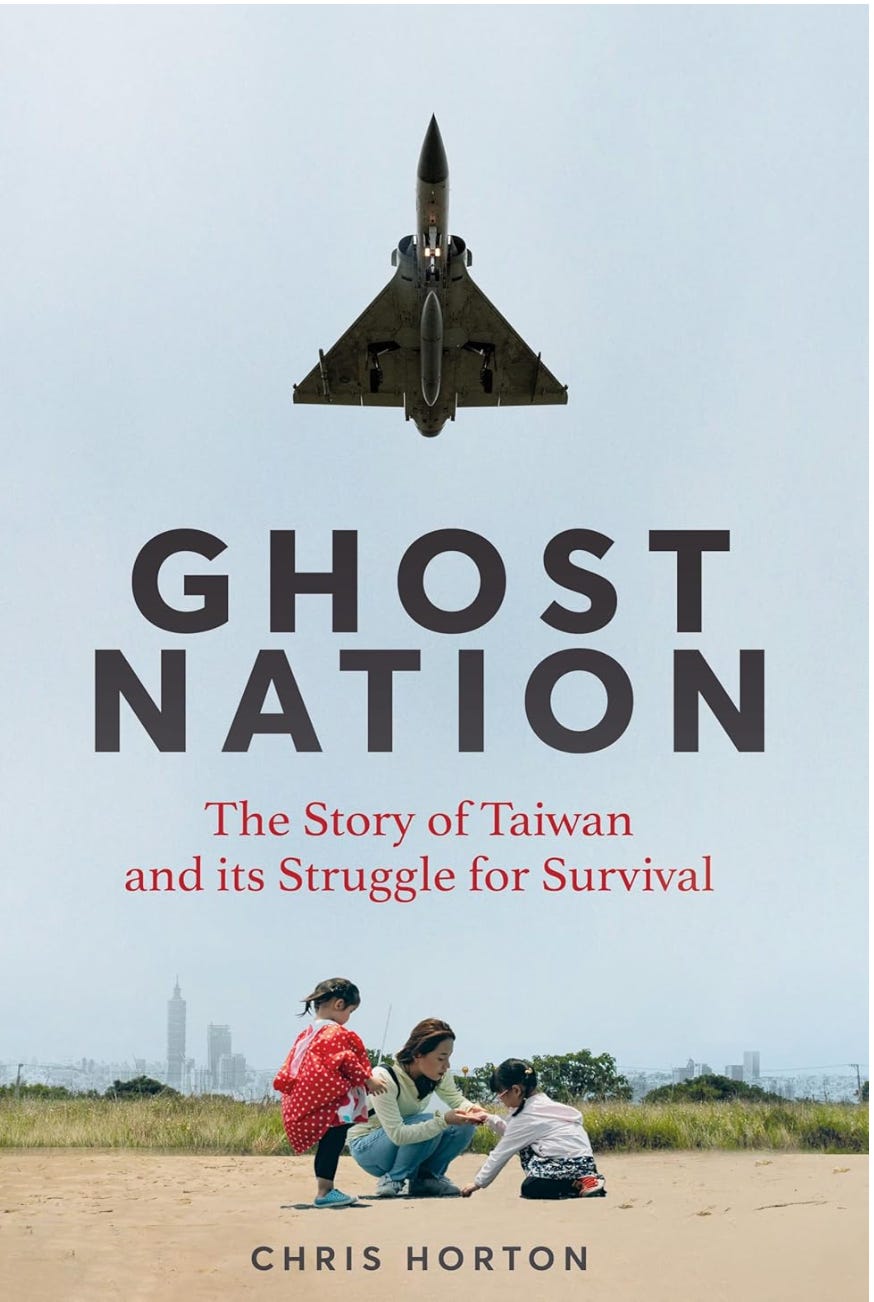

Ghost Nation: The Story of Taiwan and its Struggle for Survival

Chris Horton

Publisher : Macmillan UK

Publication date : February 10, 2026

Language : English

Print length : 336 pages

ISBN-10 : 1035034026

ISBN-13 : 978-1035034024

IF IT FEELS LIKE LIFE pummels you harder with every passing day, spare a thought for Taiwan President Lai Ching-te, urges writer Chris Horton, in the opening salvo of his engaging new release, Ghost Island.

Taiwan’s recently tottered into the ranks of superaged societies with over 20% of its population aged 65 or older. Add to that one of the world's lowest fertility rates. It’s a demographic shift that’s created widespread labor shortages across government, military and private sectors.

Young Taiwanese increasingly struggle with economic hardships as living costs rise while wages stagnate, making homeownership nearly impossible. The ruling Democratic Progressive Party bears the brunt of this frustration after nearly a decade in power.

Taiwan’s semiconductor industry, led by TSMC, demands enormous electricity and water resources, straining infrastructure already challenged by climate change and frequent droughts. Nuclear power remains politically contentious despite its potential benefits.

And then, as Horton puts it, there’s China …

Taiwan’s assertive giant to the west—a rising nation with grievances—daily escalates its pressure campaign on its diminutive neighbor. Fighter jet incursions, cyberattacks on government and private institutions, and disinformation campaigns are routine. Chinese vessels regularly steal resources from Taiwan's waters and are linked to undersea cable sabotage.

Beijing’s cognitive warfare promotes three key messages: Taiwan belongs to China, America is a fickle ally, and peaceful surrender offers the only path to preserving current freedoms.

Notes Horton:

Although the PLA Rocket Force is untested in actual combat, it is considered world-class. In any areas where China lags behind the US, it is quickly closing the gap – including its nuclear arsenal, which is being built up rapidly and in extreme secrecy. As Beijing intensifies pressure on Taiwan across various domains, Chinese military planners are clearly preparing for more than a simple confrontation against its smaller neighbour. Using the vast, sparsely populated regions in western China for exercises, the PLA Rocket Force has conducted long-distance missile attack simulations on targets that resemble American and Japanese warships.

China warnings are stark: severe consequences for Japan, the Philippines, and Australia if they dare support Taiwan or the United States during any future conflict. Beijing’s intimidation tactics became chillingly explicit in 2023 when China's ambassador to the Philippines delivered a menacing message to Manila: think twice about allowing American military access to northern bases near Taiwan if you value the safety of 150,000 Filipino workers currently in Taiwan.

While Taiwan remains China's primary objective, the United States sits in Beijing's crosshairs. China’s arsenal extends far beyond conventional military forces. The notorious Chinese cyber group Volt Typhoon has successfully penetrated critical American infrastructure networks, compromising ports, water treatment plants, and oil and gas facilities. These digital intrusions specifically target strategic locations like Guam and Hawaii—essential staging areas for any potential U.S. military response.

Creating chaos within the US economy and general public before or during an attack could buy China crucial time to establish a foothold, making takeover inevitable before American forces could even respond. Growing ties between China, Russia and North Korea raise the specter of coordinated actions: Russia targeting NATO members, North Korea provoking South Korea, and China invading Taiwan simultaneously—overwhelming US military capabilities.

In short, any Chinese assault on Taiwan would likely escalate into regional war. War games consistently predict massive casualties regardless of outcome, with potential nuclear brinksmanship. Bloomberg estimates such conflict would cost $10 trillion globally—10% of world GDP—dwarfing COVID-19's economic impact—and let’s not imagine that we’ve bounced back from that disaster.

We're still recovering from the pandemic, and that’s only the beginning of our troubles. The global economy is teetering with the weakest half-decade of growth in at least 30 years, while J.P. Morgan sees a 40% probability that the US/global economy will enter a recession by the end of 2025. The number of developing economies in debt distress was at the highest level since 2000, creating a powder keg of financial instability.

Meanwhile, the world burns with violence. Conflict levels have almost doubled in the past five years, from 104,371 conflict events in 2020 to nearly 200,000 this year. Political violence increased by 25% globally in 2024 compared to 2023, with 223,000 people killed. In the beginning of 2025, conflict event rates are expected to grow by 15% due to more bombings and battles, resulting in approximately 20,000 reported fatalities per month.

Ukraine bleeds as the world's deadliest conflict continues its brutal grind. Gaza remains buried under rubble with over 45,000 Palestinians killed. Sudan's civil war has created one of history's largest humanitarian catastrophes, while Myanmar's chaos involves 170 distinct armed groups weekly. The Sahel explodes with jihadist violence, Mexico's cartel wars claim thousands, and Haiti descends into gang-controlled anarchy.

This volatile landscape makes any Taiwan conflict potentially catastrophic—a final domino that could flatten an already recumbent world order.

It may not sound that way, but at the heart of Horton’s book is the story of Taiwan. Haunting its sidelines is the question, why on earth would Xi Jinping want it—a small island with a population smaller than Australia’s—so badly he’s willing to risk essential global stability to make it his own?

China’s already a global power with the world's second-largest economy. Why risk everything for a mountainous outcrop the size of Belgium that Beijing has never controlled?

Two compelling reasons drive Xi's obsession—perhaps if we factor in his father complex there’s a third—both centered on power, runs Horton’s thesis. First, Taiwan would transform China’s strategic position overnight. Currently trapped behind the First Island Chain—a democratic barrier including South Korea, Japan, and the Philippines—China's coastline remains confined to shallow waters where its submarines are easily tracked. Seizing Taiwan would instantly make China a Pacific power, allowing submarines to disappear into deep ocean trenches right off Taiwan's coast.

More crucially, Taiwan sits at the intersection of the Pacific, Sea of Japan, and South China Sea—the world's busiest waterways. Beijing could control global commerce flow, turning the tap of international trade on and off at will.

Second, conquering Taiwan would elevate Xi above Mao as Communist China's greatest leader while crushing Asia's most vibrant democracy. If America failed to defend Taiwan, Asian allies would likely shift toward Beijing, democracy would recede across the region, and China would emerge as the dominant Asian superpower.

OK, next question: why not just fold? Why would Taiwan resist? Horton replies:

Within living memory, the Taiwanese people have endured levels of repression and fear of state retribution similar to those faced by Chinese citizens today. This is one of many reasons that the Taiwanese population overwhelmingly reject any union with China.

For many Taiwanese, any animosity towards China is aimed primarily at the CCP, not the Chinese people. The Taiwanese are acutely aware of the long journey to freedom, having once been even more isolated and politically indoctrinated than China is today.

In the course of my [Horton’s] reporting in Taiwan, both older and younger Taiwanese have expressed sympathy for their Chinese neighbors. Whether from first-hand experience or through stories told by elder relatives, the Taiwanese see echoes of their recent dark past in Xi Jinping’s modern China.

One of Horton’s strengths is his focus on the waves of people’s that made the island their home.

Horton does an outstanding job of elucidating the growing acceptance of Indigenous people in Taiwanese society—how they've gained new political importance as living refutations of Beijing's territorial claims on the island.

Their rhetorical power blazed forth in January 2019, when leaders from two dozen tribes issued a devastating response to Xi Jinping's speech calling Taiwanese “compatriots” while threatening military force. Days after Xi's hyper-nationalist address at the Great Hall of the People, Taiwan's first peoples delivered their counterpunch, in the form of a letter.

Once called ‘barbarians,’ we are now recognized as the original owners of Taiwan. We, the Indigenous peoples of Taiwan, have pushed this nation forward towards respect for human rights, democracy and freedom. After thousands of years, we are still here.

We have never given up our rightful claim to the sovereignty of Taiwan [. . .] Nevertheless, Taiwan is also a nation that we are striving to buildtogether with other peoples who recognize the distinct identity of thisland. Taiwan is a nation accommodating diverse peoples trying to under-stand each other’s painful pasts, as well as a nation in which we can tell our own stories in our own languages, loudly.

In a world in which Chinese and Taiwan have become equivalent, a hypothetical Austronesian empire would stretch from Madagascar to Easter Island, encompassing Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines, New Zealand, Hawaii, and countless Pacific islands. This empire would house nearly half a billion people and cover more area than any country on Earth.

This review of Ghost Nation glosses over the enormously important Japanese colonial period—we’ll look at that later in the review of Taiwan Travelogue (below). Let’s jump now to the Nationalist, KMT era.

To paraphrase Horton, China’s honeymoon in Formosa lasted exactly six weeks. Taiwanese writer Ong Thiam-teng captured the initial euphoria in August 1946: “We Taiwanese were extremely happy when the pillar of [Japanese] imperialism crumbled... with an excitement as if we could reach heaven in one step.” But reality crashed down hard. “We are now like a ship without oars, floating in the open sea,” he lamented.

Ong's transformation from optimist to “Iron Councillor”—a nickname earned for his fierce criticism of KMT corruption—mirrors Taiwan's collective disillusionment. Initially hopeful about joining the “motherland,” Taiwanese quickly discovered they'd traded one colonial master for another, arguably worse one.

The looting began immediately in September 1945, operating on three devastating levels. First came ragged soldiers grabbing anything movable from streets and villages. Next, ROC officers seized control of supply depots. Finally, Governor Chen Yi's inner circle devoured Japan's massive agricultural and industrial stockpiles, leaving Taiwan's economy in ruins within a year.

The KMT didn't just steal public assets—they confiscated private homes and family property, creating "ill-gotten assets" that remain a explosive political issue today. What began as liberation became systematic pillaging, transforming Taiwanese joy into bitter resistance.

On a bitter February evening in 1947, a widow selling cigarettes outside Taipei's Pegasus Teahouse sparked a revolution that would define Taiwan's destiny. When Officer Yeh Te-ken struck Lin Chiang-mai with his gun butt for selling contraband cigarettes, then Officer Fu Hsueh-tung fired into the enraged crowd, killing a bystander, they lit the fuse of an island-wide rebellion.

By February 28th, 2,000 protesters marched through Taipei carrying banners demanding "a life for a life." They ransacked the Monopoly Bureau, beating Chinese staff to death and setting the building ablaze. When soldiers fired from rooftops into the crowd, protesters stormed the radio station, broadcasting in Taiwanese for the first time since Japanese rule: "Instead of starving to death, we should stand up and fight."

Within hours, all of Taiwan erupted. For a brief, intoxicating moment, the Taiwanese people controlled their homeland. Students, workers, and shopkeepers suddenly found themselves running the island while terrified Chinese officials cowered indoors.

But Chen Yi was already summoning reinforcements from the mainland. On March 8th, two battalions landed at Keelung, beginning the massacre Taiwanese still call "ererba"—228. The slaughter that followed would haunt Taiwan for decades, creating the foundational trauma that would eventually forge an unshakeable determination: never again would Formosa submit to Chinese rule.

Taiwan/Formosa had undergone trauma after trauma and would never be the same again. Yes, the Japanese were colonial occupiers. To see the Chinese in the same light would alter Taiwan’s relationship with its vast neighbor forever.

Chen Yi and the KMT had retaken control of Taiwan. While state propaganda initially boasted of successfully suppressing the 228 rebellion, it would quickly switch to suppressing the memory of 228. In the thirty-six years between 1948 and 1984, major newspapers in Taiwan only mentioned 228 four times. It wasn’t until the end of martial law in 1987 that the Taiwanese finally began to feel safe to discuss 228.

The 228 Incident—or the fact that had reclaimed a place on the public agenda—arguably created post martial-war Taiwanese identity. As the KMT lost mainland China, it had chosen to terrorize Taiwan's people, setting them on a path of determined resistance that would eventually forge today's vibrant democracy.

International media now calls the KMT Taiwan's “largest opposition party,” a shorthand that glosses over its dark history. The KMT denied an entire generation basic democratic freedoms, keeping 228 out of public discourse to maintain its right to rule. Everyone knew American support enabled Chiang's atrocities while Washington kept criticisms of its anti-Communist ally muted and private.

Just as 228 catalyzed decades of Taiwanese oppression from 1947 onwards, the eventual public reckoning with these massacres became the foundation for one of the world's freest democracies. Taiwan’s democracy didn't emerge despite 228—it emerged because of it.

The 228 massacres forged modern Taiwanese identity. Losing mainland China, the KMT chose terror over governance, inadvertently setting Taiwan on a collision course toward the vibrant democracy that would eventually—through extraordinary struggle and luck—emerge decades later.

The media casually scripts the KMT as Taiwan's “largest opposition party”–but that’s glossing a hugely complex problem.As the KMT lost mainland China to Mao's Communists, the KMT inadvertently set Taiwan on a collision course with democracy that would eventually—through extraordinary struggle and luck—emerge decades later.

Ghost Nation's true strength lies not merely in revealing Taiwan as liminal—an uncertain space, an indistinct identity—but in its telling of the story of how Taiwan triumphed over forces that might have erased it entirely—still threaten to do so.

China's vision is one of imposed uniformity, the antithesis of the diversity that defines Taiwan's essence. The odds, admittedly, favor the colossus—we remain too mesmerized by the Middle Kingdom's ascendant power, too fearful of its reach and its ever-threatening military might. Yet beyond the familiar democracy-versus-autocracy narrative lies something more profound: Taiwan's singular courage to confront its own darkness. In a world increasingly defined by selective memory and manufactured histories, Taiwan's willingness to face its ghosts marks it as both brave and irreplaceable.

If we must choose, we would obviously choose democracy over authoritarianism. But democracy is not easy—just as the messy, painful, essential work of confronting truth is so much more difficult than the seductive comfort of forgetting.

Ghost Nation occupies a unique place in this landscape. It confronts the past not as an educational exercise aimed at expanding our horizons, but as a reckoning with uncomfortable truths, preferably shelved, forgotten.

If China is a self-aggrandizing fabrication of power. Taiwan, by contrast, is what Horton describes as the land of hungry ghosts—visible yet unacknowledged, vital yet unwelcome. Every seventh lunar month, usually in August or September, the gates of hell open and these ghosts—spirits without descendants or proper burials—are released to wander among the living, desperately seeking food and care.

Colonial rulers once banned Ghost Month's ceremonies, perhaps sensing how these wandering spirits reflected their own failures to care for the island's people. Today's Taiwan embodies this spectral existence on the global stage. One of the world's wealthiest democracies, the semiconductor powerhouse of our digital lives, yet its president cannot enter most foreign capitals or speak at international forums. The island floats in diplomatic limbo—too important to ignore, too dangerous to embrace.

The absurdity? Taiwan's isolation stems not from Chinese pressure alone but from our own calculated indifference. While Beijing threatens and blusters, democratic nations have quietly ghosted Taiwan for decades, seduced by mainland markets and terrified of confrontation. We are the perpetrators of this phantom state, maintaining a thriving democracy at arm's length while profiting from its innovations.

This comfortable arrangement may not endure. Our refusal to fully recognize Taiwan's legitimacy risks consequences far graver than diplomatic protests—potentially sacrificing a free society to appease authoritarian ambitions.

Yet Taiwan remains as scrappy as it is inventive—more inclined to legislative fistfights than rubber-stamp approvals for a third tenure of any Great Helmsman. Sadly, the price it may pay for this democratic unruliness could be obliteration as a political entity.

Ghost Nation fascinates to the extent it brings Taiwan to life more vividly than any recent work; it terrifies insofar as it sketches Xi Jinping's final "solution"—a playbook in which diversity and inventiveness, the refusal to fall into lockstep orthodoxy, wins nothing but authoritarian punishment.

What we can only hope is that Ghost Nation, an important book, as another book written by an American obsessed with Taiwan was in its day, will not become the prolonged obituary that Formosa Betrayed became and still is.

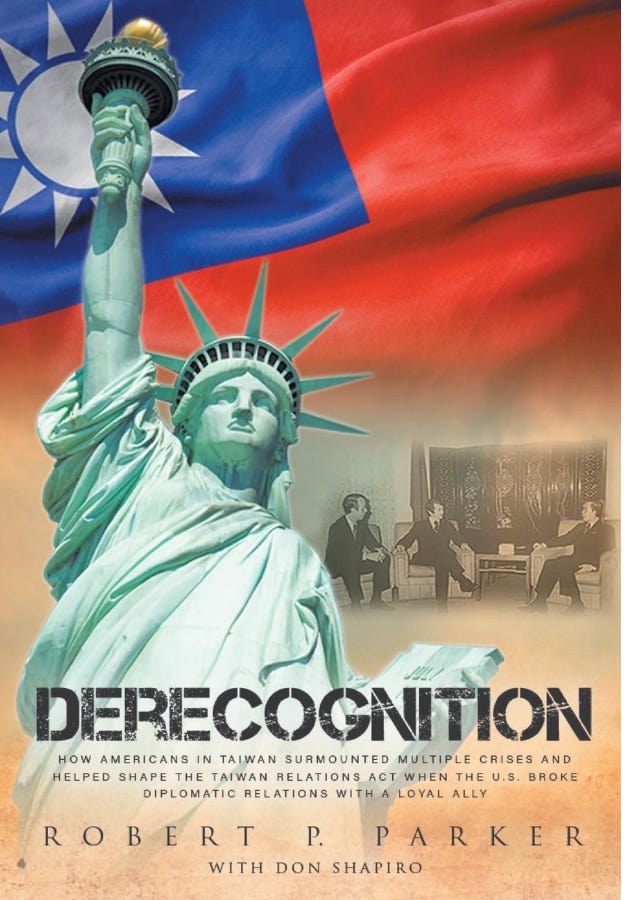

Robert Parker, with Don Shapiro

Publisher : Bookside Press

Publication date : April 9, 2025

Language : English

Print length : 198 pages

ISBN-10 : 177883616X

ISBN-13 : 978-1778836169

ON THE MORNING of December 16, 1978, President Jimmy Carter delivered a shock blow to Taiwan: Communist China was now the sole legitimate government and the US would terminate all diplomatic relations with Taiwan, effective January 1, 1979.

It was the end of a three-decade, client state relationship—a Cold War protectorate relationship if you’d prefer—turning to the “unsinkable aircraft carrier” (as MacArthur called it), depending entirely on US backing for legitimacy and security.

The US also provided massive financial assistance, maintained military bases and advisors on the island, and Taiwan essentially operated under American security guarantees through the Mutual Defense Treaty.

But Taiwan was the junior partner relying on American patronage for its very survival—and its situation was even more precarious after losing the mainland to the Communists.

Taiwan's President Chiang Ching-kuo—son of Chiang Kai-shek—faced this betrayal with remarkable determination, vowing to transform crisis into opportunity through self-reliance. American businesses, residents, and Taiwan's entire future hung in diplomatic limbo.

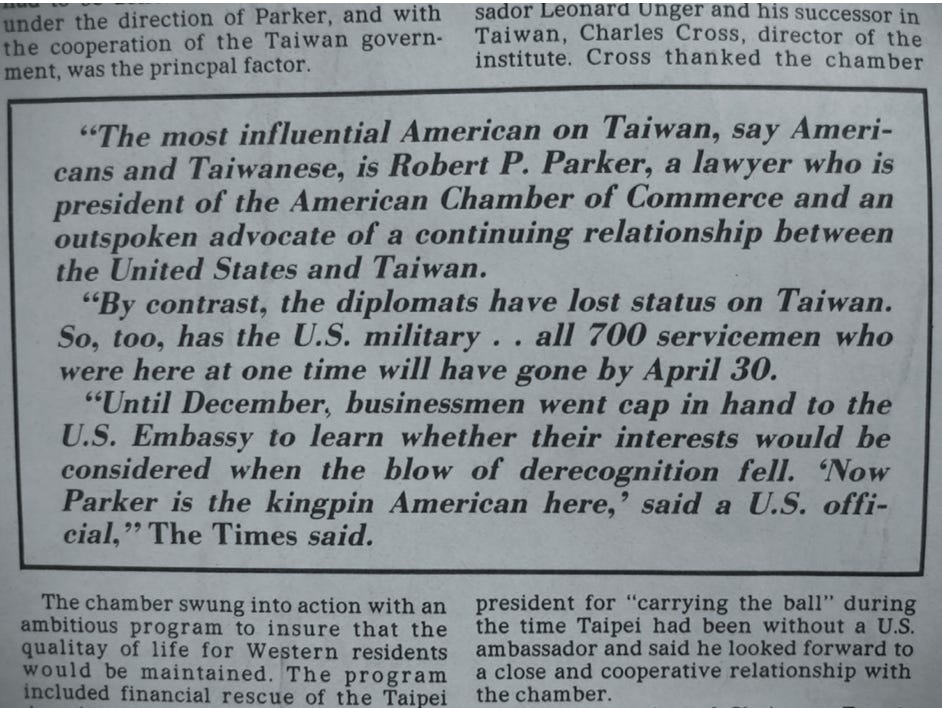

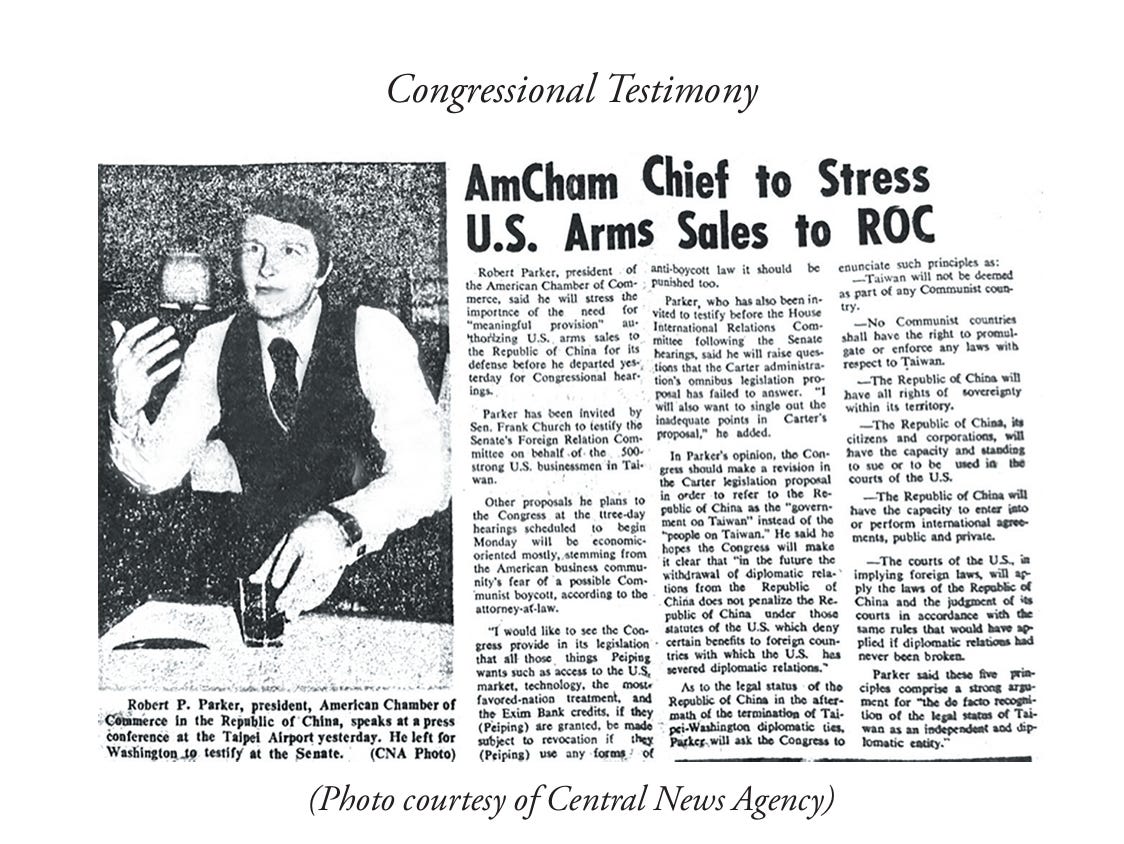

Another—and far more surprising player in the upheaval is one —Robert Parker, a lawyer heading an international firm in Taipei and newly elected president of the American Chamber of Commerce, you’re forgiven if you’ve never heard of him. Yes, a relative unknown other than to a few outsiders, Parker mobilized to protect American interests and Taiwan's welfare. His testimony before Congress transformed the State Department's inadequate “omnibus bill” into the robust Taiwan Relations Act, signed into law April 10, 1979.

The timing was right. Taiwan was engaged in engineering an economic miracle, transforming iteslf through massive infrastructure investment and technological development. It attracted luminaries like Patrick Haggerty from Texas Instruments and Bob Evans from IBM to guide a high-tech revolution. Former students returned from abroad, creating the electronics powerhouse that would transform Taiwan into the global supply chain powerhouse it’s known as today.

Within two decades, an island, a territory, a state, a country … a state of mind? that proclaimed itself “Free China” until the words began to ring hollow, out of tune with the impossible reality the new Taiwan had become.

By 1997, the IMF reclassified Taiwan from “Newly Industrialized” to “Other Advanced Economies.” Asian Business Week captured the extraordinary transformation in a front page-grabbing headliner: “Why Taiwan Matters? The Global Economy Couldn't Function Without It.”

Parker's Taiwan Relations Act endures forty-five years on, proving that American betrayal inadvertently forged Taiwan's greatest strength—the determination to survive and thrive alone. What began as diplomatic abandonment became economic independence, creating a democracy too valuable for the world to lose.

Carter the sellout—peanuts and friends

On its renunciation:

Taipei was ablaze with banners denouncing Carter, some in English, most in Chinese. A sign festooned along a median fence near my office on Zhongshan North Road read: “Carter Sells Peanuts. Also Friends.”

Carter may have been the nexus of Taiwan fury, but as Don Shapiro, a veteran Taiwan expert (and coauthor of this book), puts it in the words of Robert P. Parker:

With the Chamber’s board and committees hard at work on the four local projects, I concentrated on preparing for the mission to Washington, to present AmCham’s position on what would become the Taiwan Relations Act.

Many foreign reporters based in Taiwan, myself included, consider the way most international publications dodge Taiwan’s undeniable sovereignty indefensible. But for Taiwanese journalists working for international media who are forced to deny their country’s statehood, this wilful denigration of their government is not just a professional issue, but also a personal one.

‘As someone born and raised in Taiwan, it definitely sucks,’ one Taiwanese journalist told me. ‘But it’s also part of being Taiwanese – you see Taiwan as its own country growing up, until you experience the wider world, and then you see its statehood denied.

The details:

Among the institutions vital to expatriate life in Taiwan, English-language radio was the one in greatest jeopardy from derecognition. Taipei American School would carry on in one form or another, the American Club would continue as a haven for families in one location or another, and parents would find places for their kids to play games, but the only English-language broadcasting station in Taiwan was about to permanently shut down and its broadcasting equipment taken away to be scrapped.

A Radio Station by Any Other Name

Parkers tale–and in honesty, it’s homespun, very Taiwan, even if it it touches on issues of global significance. The passages on ICRT, for example, Taiwan claiming an English-language radio station to it own with more freedom than anything broadcast in Taiwan before, is of course important, but far more so to insiders than to outsiders. But that’s not to gloss over what it brought to Taiwan:

In the decade that followed, audience surveys showed year after year that ICRT attracted more than a million listeners. The non-profit station became a commercial success contributing to environmental, women’s rights and other worthy causes. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, other Taiwan stations copied ICRT’s innovations, and the rise of satellite broadcasting and the internet inevitably reduced the size of radio’s overall audience. In 1979 and throughout the 1980s, however, ICRT was the cultural lifeline of Americans in Taiwan. Moreover, as James Soong told the authors in an interview for this book, "‘If we didn’t have this English-speaking radio [station at that time], we would have been cut off from the outside world.’

Derecognition reads like a yearbook of a vanished world—a tender catalog of an American community that once flourished—in Taiwan, as it happens—now preserved only in institutional memory. It's the memoir of an expatriate enclave that had to transform itself overnight when the diplomatic ground shifted beneath its feet, leaving behind a detailed record of how a displaced community negotiated its survival.

The focus on Taipei American School captures something poignant transplanted slice of America, complete with parent-elected school boards and familiar curricula, suddenly orphaned when the treaties that protected it disappeared. The book becomes a kind of institutional archaeology, documenting the delicate work of transforming official ties into “unofficial” relationships—the minutiae of relocating schools from flood-ravaged campuses, negotiating radio station licenses, preserving the American Club's social fabric.

There's something deeply surreal about reading these intimate, human-scale stories of a community learning to survive diplomatic abandonment. Parent-teacher committees and campus flooding concerns, the careful bureaucratic dance of maintaining American institutions without American protection—all preserved with the meticulous care of a school annual, complete with the awkward formality of official photographs and the underlying melancholy of something irretrievably lost.

Yet this small island that America formally abandoned in 1979, this place reduced to yearbook memories and institutional workarounds, now sits at the center of what could become the most consequential geopolitical crisis since the Cuban Missile Crisis. The same Taiwan that had to reinvent its American school because it lost diplomatic protection has become the potential flashpoint for global catastrophe, the place where World War III might begin.

It's like discovering that the forgotten high-school town of your shadowy memories now powers the digital backbone of your ephemerally interconnected office life—maybe WWIII, IIII even, who can keep count?

Derecognition sneaks up on the reader. Everyone’s supposed to love Jimmy Carter, but what if in his avuncular generosity, he underestimated the power he ruled over—and even more terrifyingly the power that was to become its arch enemy, China. There was a time, after all, in which it was right to give the downtrodden Middle Kingdom a long-denied shot at the place in the world in deserved.

Whatever might be said about the US, it has so far managed to avoid leading us into a war of globally catastrophic proportions—although that may be luck.

China may be less lucky. Derecognition then would be a disaster—slow in the making, probably, but very fast in its unravelling, to paraphrase Hemingway.

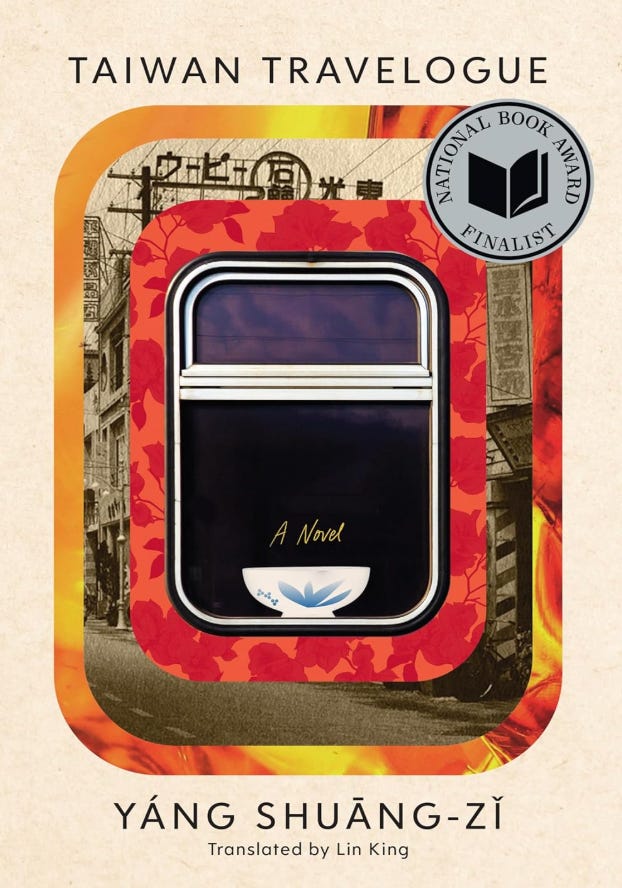

Yáng Shuāng-zǐ, Translated by Lin King

ASIN : B0D9F5ZHL4

Publisher : Graywolf Press

Publication date : November 12, 2024

The ghosts of Yang Shuang-zi’s Taiwan Travelogue are separated by more than a century from Chris Horton’s Ghost Nation—half a century removed from the dispossessed of Derecognition. The places these three books occupy are displaced in time, recognizable, and yet vastly different.

The Japan of Taiwan Travelogue—having lost WWII—is, for example, the ravaged nation that has no choice but to hand over its colonial baton to the defeated Nationalists of China, the latest in Taiwan’s long string of colonizers. It jars for the modern reader familiar with Tawan and China to see the word “mainland” and realize it refers to Japan, but Japan had that moment.

Meanwhile, there’s far more trickery going on in Taiwan Travelogue than the antics of the ghost world. The entire book is a literary prank—an arch play on the reader that has, perhaps ironically, perhaps not, won awards for translation—the US National Book Award for Translated Fiction is one—and yet its provenance as translation? It’s more like fiction in multiple languages—chiefly, Taiwanese, Chinese and Japanese—and in the edition reviewed by this reader written in English

Was Taiwan Travelogue the work of an imagined Japanese writer–the Great Cedar, as she calls herself, despite her less than towering height (itself a poke at the burgeoning Japanese empire?) Was she an imagined Japanese ahead of her time, intellectually attuned to colonial 1938 Taiwan? Was the Japanese manuscript lost, found by an adopted daughter, who sent it to the character's daughter before translating it into Chinese.

No.

The actual author Yang Shuang-zi says she and her sister “wrote” the the English translation—is the word “wrote” deliberate, a further word play, even though the translator is Lin King?

The pen name associated with the book suggests it’s written by twins (shuangzi, the given name, although why both twins would be given the name “twin” suggests only a pun). They’re not twins. More mercurial mystification. But the book is inspired by the love of a twin. I’ll let the Japan Times step in:

Yang Shuang-zi is the pen name of Yang Jo-Tzu, 40, a native of Taichung, Taiwan. The word “shuang-zi” means “twins” in Chinese (written with the same kanji as the Japanese word “futago”) and pays homage to the late Yang Jo-Hui, Jo-Tzu’s twin sister who passed away from cancer in 2015.

But to return to the metafiction at play here—as dense at times as the roiling descriptions of the dishes that litter the book (has ever a book relished in the act of eating as much as Taiwan Travelogue? The answer, this reader and reviewer will suggest is a decided no). Forgive the suggestion, but this really is the Marquis de Sade of the culinary world, but with better taste, and don’t feel obliged to forgive that pun.

Certainly, no other book has ever done such an all-consuming job of extolling the cuisine of Taiwan—no room here for the regional cuisines of China.

But to return to the metafiction, the fictional Japanese voice that bestows its love on the gastronomy of Taiwan is convincing enough for the book’s many readers to come away convinced that the author is who she’s claimed to be.

But in the end our Japanese author is a fictional Japanese colonizer through whose eyes Yang explores themes of power, translation, and colonial relationships.

Aoyama Chizuko does not exist and never existed. She is entirely a fictional character created by Yang Shuang-zi.

The entire literary conceit–a retrieved Japanese travelogue that is fictional, no original Japanese text, no historical Japanese author named Aoyama Chizuko, no real travelogue from 1938. The itself is almost a ghost:

The term wānshēng originated when Taiwan was under Japanese colonial rule, and its meaning is exactly what the Han characters imply: Japanese people born in Taiwan. By blood we belonged to the great Yamato race, but as Japanese citizens we were “subpar”; growing up on the subtropical island, our use of the national language, Japanese, was often nonstandard, and few of us had ever seen snow or truly experienced the four seasons …

In many senses, the wānshēng are homeless, casteless ghosts. However, there are perspectives to which only ghosts are privy. For instance, there are certain things that only we ghosts [the ghosts of a Japanese empire past, or other past would be empires over Taiwan?) would notice within Aoyama Chizuko’s novel.

Who those ghosts are and what it is they might be able to elucidate to us is never made clear–or this reader missed a crucial nuance—but Taiwan is still to this day, marginal, ghostlike, a liminality that lacks the luxuries of identity taken for granted by most other nations—today claimed by a giant neighbor it will be hard pressed to keep at bay forever.